Should Students Get Paid for Being in School?

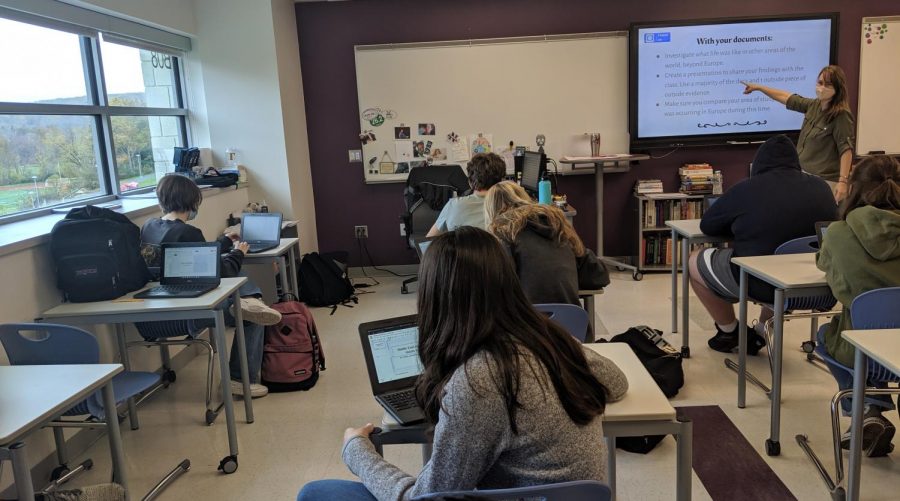

Social studies teacher Rebecca Trzaski addresses a freshman world history class Oct. 27. Trzaski is one opponent of an idea to compensate students for their time in school.

October 27, 2021

It’s no secret that even though kids in America have the privilege of going to school, not all of them appreciate it. Parents constantly hear complaints like, “I don’t want to go to school today,” or, “School is useless, I get nothing out of it.”

But what if these complaints were taken to the extreme? What if students were paid to go to school?

People have varying opinions about this subject. Students are both reluctant and passionate about the idea, saying things like money might motivate them to get out of bed in the morning. However, they mostly agree that it wouldn’t be a good idea in the long run for various reasons.

“I wake up very early in the morning to go somewhere that I don’t really enjoy going to,” Nonnewaug freshman Alexa Celello said. “But paying kids still isn’t a good idea because the pay wouldn’t be equal. It would be wrong to pay someone who slacks off the same amount as someone who works hard.”

“You go to school for your own good and success,” junior Lux Calo agreed.

Even though Calo and Celello are at different stages of their academic career, they both agree that students should be motivated by their own will to learn.

“It doesn’t make sense to be paying someone for something they should be doing for themselves anyway,” Calo said.

Celello and Calo certainly did not want teachers to pay out of pocket, but they also stood their ground even when it came to the idea of the district paying students to learn.

“No matter who’s paying for it, I don’t think it should be something you get paid for if it’s helpful for you,” said Calo.

“I guess it’s better than teachers paying for it themselves, but I don’t think that’s a good way for the district to be spending money,” said Celello.

Positive behavior reinforcement is something that was practiced on many of us when we were young. What if that were the reward for cooperative learning instead, like kids frequently being given candy or getting to watch movies in class?

Celello’s answer was simple: “It sounds nice to be rewarded, but I think school should just be a place to learn and nothing more.”

Calo agreed that positive reinforcement is helpful.

“I think that’s a really good method that teachers can use because it motivates us to try harder,” Calo said. “Unlike paying money, letting kids have fun is occasional.”

Tony Jiang, an author from The Decision Lab, has a different opinion. He believes that students sometimes have no choice but to drop out of school. Since there are so many benefits to continuing school and getting a degree, Jiang feels that paying students might be beneficial so that they can continue.

“Incentivizing students could allow them to put more effort into attending school and to care more about their studies, at least for long enough that they can complete their degree,” he wrote.

The author also mentions how the payment could help to support lower-income families.

“This could particularly offset the challenges faced by students who come from financially disadvantaged backgrounds, as monetary incentives would allow these students to focus on their studies and not require an outside job, therefore reducing the probability of dropping out,” Jiang said.

Rebecca Trzaski, history teacher at Nonnewaug, provided her firm rebuttal to Jiang’s counterargument.

“That is the most asinine idea I’ve ever heard,” she said. “No. At what ages would kids start getting paid? What would we be paying? How can we fund any of this? At some point, this would make it so that my students are making more money than me! The sentiment is nice, but I try to stress to my own children, they’re not the ones with bills to pay.”

“They don’t have to pay rent, they don’t need to worry about healthcare; their job is to work hard in school with the belief that that will put them in a better position,” Trzaski continued. “My salary barely covers my cost of living. If I’m supposed to pay all my students, I would simply not be able to cover all my necessities.”

When asked about her opinion on a separate budget from the district, she said there are already financial incentives for students.

“In a way, schools already do this. There are plenty of scholarship opportunities out there,” Trzaski said as she pulled out her calculator and began doing the math. “Let’s say we paid each kid the minimum wage. Our school would need to come up with another $29 million, which is about what we have currently. At a school like Pomperaug, they would need another $79 million just to pay kids minimum wage. This obviously surpasses the tax threshold, so the kids would be giving back taxes to the government that don’t count towards property taxes because they don’t own their own properties. It’s just financially not feasible.”

When asked about positive behavior reinforcement as a reward, Trzaski said that she would first have to see how effective that is.

“I know elementary schools do that a lot, but I think it’s an unrealistic expectation,” Trzaski said. “You do get rewarded for your work — grades. If you do your job correctly, you get a good grade. And if not, you don’t.”

“The realistic expectation is that now that I’m in the workforce, I don’t get rewarded for being a good teacher everyday,” she continued. “Most people in the workforce get paid weekly or biweekly. Positive reinforcement is used in elementary schools because young children cannot put into perspective what the endgame is. Everyone in a classroom is there because someone else is paying for them, and that is a reward in itself.”

Trzaski provided a final example as to why the compensation plan would be absurd.

She asked: “Do I think that my 3-year-old should be earning $11 an hour to color pictures?”