Cole: AI and Writing as a Product of Living

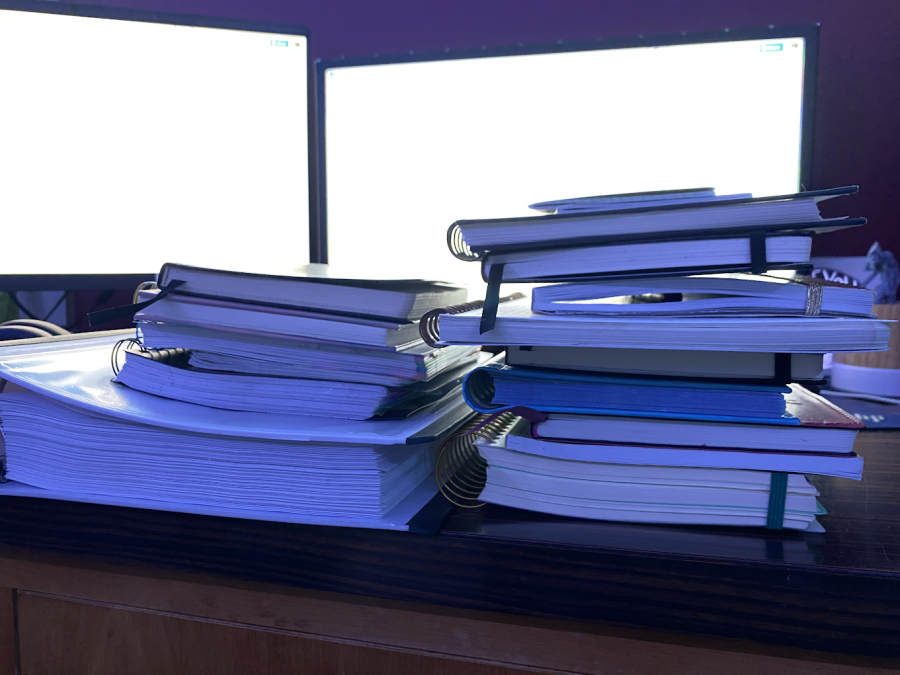

A certain sense of satisfaction can be found in a single journal full of experiences. Or two. Or twelve.

February 14, 2023

WOODBURY — Life revolves around words. Understanding them, hearing them, speaking them — reading and writing them, like you and I are now — are all things we need to be able to do.

As a writer myself, I’ll admit that some of my own designated writing time isn’t spent writing, be it academic or not.

Alright, fine. Most of it isn’t spent writing.

Once I conquer the strenuous task of actually turning on my computer, or digging up a pen that still has ink in it, it’s like the student in me wakes up from whatever after-school slumber she’s fallen into. She lunges out of the passenger seat and grabs the wheel of my little brain-car, screaming, No! This isn’t being graded! Nobody’s making us do this!

So, to keep us both from spinning into a metaphorical guardrail, I’ll stand up again before I’ve written a single sentence. The little word-count box in the corner of my screen stares at me, and I stare back, sighing, before scurrying out of the room to go find one of the cats.

And get a glass of water.

And make something for lunch.

And fold my laundry, because I’m already out here, right?

And wow, that brownie mix has been sitting in the cabinet for a year now, but suddenly I could go for something sweet.

And it all ends where it started; I’m sitting at my desk, with an hour behind me and absolutely nothing done. I’ll try to glance at the word count (maybe it’s magically gone up), but now the cat knows I’m trying to get work done, and he’s sitting on top of the keyboard with a look that says, You’re not using it, anyway.

It’s this simple: words are tools. Burdens — to students, at least — that take the shape of a word count or a page count that demands to be met before anything else can be done (just keep taking apart those contractions — you’ll get there).

But these tools don’t always have to be used for school or work. To those who find value outside the implications of a five-page-minimum essay, words are building blocks — paints fit for a thin page of lined 8.5-by-11-inch paper.

Maura White, an English teacher at Nonnewaug High School, understands the many benefits writing offers.

“I write poetry outside of school,” she said. “It really helps me connect with my creative side and experience life more fully.”

It’s an act of creation. It’s a way of putting thoughts into words on paper, and, in a way, leaving yourself on the page. It’s a way of preserving feelings, freeing them to be manipulated in any way a story demands.

In fact, the act of creation that writing demands is an act of humanity; creating art is, in a way, art itself.

Sure, this might be what I tell myself when I feel bad for spending an hour of writing time not writing, but it also happens to be true. All of the little things that live in paragraph breaks, indents, and those blank spaces between 12-point Times New Roman words are a part of the process.

“The world can be such an amazing place,” White said, “and anything can be inspiring. Beauty, pain, even my cat and dog.”

That means the good — those bright ideas that strike right after you close your computer — and the bad, like procrastination and unmade brownies and wrinkled laundry, make recreational writing exclusively and exquisitely human.

In an era of unprecedented technological development, amidst the rapid growth of artificial intelligence, the future of human entertainment has recently been brought into question. After all, in a time when computers can study, learn, and — most importantly — write an unlimited number of new Seinfeld episodes, why should humanity bother wasting time, money, and thought on completing tasks a robot could do instead?

The answer is connection.

“Writing is a reflection of who we are,” said White. “By putting our own voices on a page, we make connections with other people. It’s like a conversation.”

Undeniably, technology will continue to advance. Chatbots like ChatGPT and its competitors might know everything about human behavior — how and why we do things like name plants and keep Christmas cards from years past.

But they will never understand what makes these small gestures so important, or why a written piece is more than just a product of a command they’re given from some faceless internet user.

“Writing is inherently human,” said Nonnewaug senior Rebecca Varnum. “Books aren’t sad because sad things happen in them — the root of the sadness is the emotions that the writer is able to weave into their words. I don’t think it would be possible to find AI that can replicate that kind of literature.”

Now, as funny as it would be for me to end this piece by dramatically revealing that this entire story was written by a chatbot, I can only offer this:

The art of using words to capture the human experience offers power unlike that which visual art conveys. It shatters the boundaries between the modern world and bygone times, and snaps the line between fiction and reality, forcing writers to truly think and feel for themselves if they hope to bring written scenes to life.

“There are no constraints on what you can create,” Varnum said. “A blank page is a place where you can be unapologetically you, and express yourself in whatever way you need to.”

It’s something beyond the true comprehension of current artificial minds: a gateway of human capability, making anything possible with only a pen and a paper.

This is the opinion of Chief Advocate assistant features editor Zoie Cole.