Playing ball in the backyard is often the first sports memory for any athlete. It’s this memory that ignites that athletic flame for some to continually pursue a dream: reaching the pinnacle of sports.

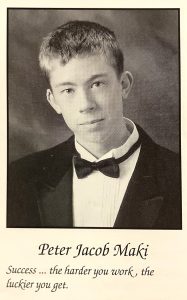

Pete Maki took his passion for baseball and ran with it. Maki, a Nonnewaug alum who graduated in 2000, has made history as he enters his second full year as pitching coach for the Minnesota Twins.

“These things take place over time. Each individual step seems like the next natural progression,” Maki said in an interview with the Chief Advocate. “When you look in terms of a big picture it’s like, ‘Holy [crap].’”

Maki’s path from Nonnewaug to Major League Baseball has been a winding one as his baseball journey began when he transferred to NHS in March of his sophomore year, moving from a small town in Pennsylvania and quickly finding his home on the baseball diamond amid this dramatic life change.

“My time at Nonnewaug, truly the first six months, was a tough time to move and make friends, so baseball really helped with that,” Maki recalled. “Baseball helped me make those connections socially. My transition would have been a lot tougher without baseball.”

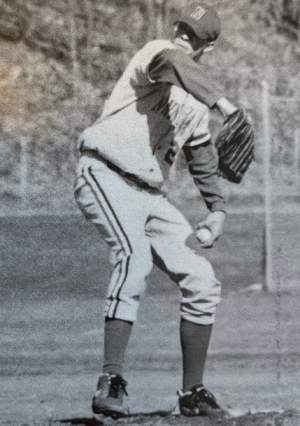

During his time at NHS, Maki’s long list of accolades and achievements began when the Chiefs went on to play in the 1999 Class M state championship, the first such appearance in school history. Nonnewaug lost to Plainville, 3-0.

“Pete was a quiet kid,” remembers Angelo Casagrande, Maki’s head coach during the team’s 1999 postseason run. “[He was] very methodical in his approach to pitching. In that, I mean he was always working to improve his pitching, and never really let his emotions influence his game.”

Even though Nonnewaug failed to win the title game in Maki’s junior season, during which he went 6-1 as a pitcher, it was clear to his coaches that he had the acumen and poise needed to succeed in baseball.

His success continued as a senior, when the left-handed pitcher earned Academic All-State honors after leading the Chiefs to the Berkshire League championship. Perhaps his best game of that season came in a 4-3, eight-inning win over defending BL and Class S champion Shepaug, an early-May win that gave Nonnewaug an insurmountable lead in the league standings. Maki struck out 12 in a complete-game effort despite falling into a 2-0 hole thanks to a pair of unearned runs.

“If you let errors in the field get to you, you’re not doing the job as a pitcher,” Maki told the Register Citizen after that game.

Maki also graduated as the class of 2000’s salutatorian.

“He was always thinking,” Casagrande added. “He didn’t just get on the mound and throw. He and his catcher were working location, velocity, pitch selection in a more sophisticated way than most high school pitchers did. His dad [Don] was an excellent pitcher and helped him enormously. I had no doubt Pete would pitch in college.”

As his high school playing career ended, that was not the last of baseball for Maki, who returned to Pennsylvania to play collegiate baseball at the NCAA Division III level for Franklin and Marshall in Lancaster. While heading the Diplomats’ pitching staff, Maki was named the team’s Cy Young Award Winner, an award given to the team’s top pitcher. Maki then parlayed his success into an invitation to the prestigious Cape Cod Baseball League and New England Collegiate Baseball League.

Despite Maki’s collegiate success that merited invitations to high-profile summer leagues, the prospect of a professional life in baseball dimmed, but for Maki, pursuing a career in baseball was something he never gave up on. He decided to coach.

“Maybe I was dumb enough, but here’s what people don’t think about when looking at coaching careers: You make no money and you have weird hours,” Maki recalled when considering a transition from player to coach. “At the time, the first five or six years of coaching, I went to college and I went into debt. My parents sacrificed money for me to go to college and I graduated, and what you are supposed to do is get a job that makes money and pay off your loans.”

Maki’s parents not only encouraged his baseball pursuits, but his father, Don, has long had a connection with athletics, pursuing his own baseball career as an athlete. Today, Don Maki assists current NHS students with track and field events. Pete’s mother, Janice, has been a part of the Woodbury community since the family moved to Connecticut in 1998. The two are still mainstays on campus and can be seen attending NHS events ranging from basketball games to school plays. Together, Pete’s parents created an environment that fostered and encouraged him to follow his baseball goals.

Juggling the balance between his baseball aspirations and the financial pressures of life beyond college, Maki moved back to Woodbury after his playing career ended, and he was back at Nonnewaug where he served as an assistant coach for the Chiefs baseball program in 2006. Immediately, it was clear to Maki’s players that he belonged on the diamond.

“He provided clear direction on ways to improve, and I also remember him not sugarcoating anything on approaches to fix bad habits on the field,” said Mark Suchin, a middle infielder who played under Maki. “When he was our coach, he was still in his 20s, which made him easily approachable and an easy coach to communicate with.”

“Maki called the pitches from the dugout when he was pitching coach,” said Mike Carlton, who played catcher during Maki’s time as an assistant. “As the catcher, I relayed these to the pitcher and his focus on the game was incredible. He knew exactly what pitches needed to be thrown and when.”

Climbing the Collegiate Ranks

After his year as an assistant at NHS, Maki’s college coach, Brett Boretti, contacted him about an opportunity at the University of New Haven as a volunteer pitching coach, which allowed him to parlay his collegiate success with his newfound love of coaching.

“I was trying to do real estate at the time,” Maki remembers, looking back at a time in his life without baseball before coaching. “I figured out I wasn’t that good at it, so I ended up at University of New Haven as a pitching coach and that’s where it started.”

While serving as pitching coach for the New Haven Chargers at the Division II level, Maki quickly found his stride sliding over from player to coach, guiding his New Haven staff to a league-best earned-run average and strikeout-to-walk ratio.

Maki turned his success into a job at the Division I Ivy League level, where he was named pitching coach at Columbia University. He guided the Lions’ pitching staff for eight seasons, a tenure during which Columbia captured multiple Ivy League titles and set school records for pitching dominance.

Winning at Columbia offered Maki yet another opportunity, an opportunity that he could only dream of: coaching at Duke University.

At Duke, Maki developed one of the Atlantic Coast Conference’s top pitching staffs as the Blue Devils earned a trip to the NCAA tournament in 2015, breaking a 55-year postseason drought. Everywhere Maki went, success seemed to follow.

“There were a lot of people at the time who said it outwardly or not and were like, ‘Damn, why are you doing that?’ – you know, making $3,000 and having to substitute teach,” Maki recalls when reliving the lean years of balancing his baseball dreams with financial realities.

As Maki ascended the ranks he began to see his investment – and love for baseball – pay off.

“People would ask, ‘What did you go to college for?’” he calls. “It’s neat now, [but] you have to make that choice when you are younger. That’s a risk not a lot of people are willing to take to do something that they love.”

A Dream Realized: Life in MLB and a “Position of Coolness”

Through each step, Maki’s résumé grew more impressive, though he never had an intention to coach an MLB team.

“If someone were to ask me in 2015 when I was an assistant coach if I was going to be coaching in the big leagues now, I would have chuckled,” Maki said. “It would have been funny to me.”

Much like any job, Maki’s ascent was gradual, but finally, in 2017, he earned the right to call himself part of a big league organization when the Minnesota Twins tapped him to join their minor league system.

“Each step after Columbia seemed like the right and the natural next step,” Maki remembers, making his continual climb up the baseball hierarchy. “[Moving from Duke to the minors] wasn’t a huge leap in itself. It’s like any other field, [similar to being] the CEO of any Fortune 500 company. People look where that man or woman is now and it seems like everyone’s impressed, but it’s the incremental steps that it took to get there. That’s how anyone gets to a position of coolness that has a wow factor. It takes time and it takes work and it takes people giving you a shot really. Certain people along the way have taken a chance on me, and hopefully I have rewarded them with some good work.”

Maki’s first role in professional baseball began as the Twins’ minor league pitching coordinator in 2018, which then segued into the Twins’ major league bullpen coaching job in 2020. When Minnesota pitching coach Wes Johnson left the team in June 2022, the club chose Maki to take his place.

“It wasn’t like I was a new guy hired from an outside organization thrusted into the top pitching job in that organization,” Maki says. “I kind of came up through the organization as a coach, so [in] that transition, there were no radical shake-ups; the framework and foundation was already in place.”

As Maki made his way up the MLB ladder, he was always a favorite among his players, establishing connections that made his job much easier. For Maki, he refined the art of building relationships during his time coaching at Nonnewaug.

“It’s not surprising to me he now coaches at a professional level,” Suchin said. “The man knows the game, and more importantly was open and giving of his knowledge to his players.”

Big League Talent, Big League Success

In February, Maki and his Minnesota pitching staff will take to the balmy green fields of Fort Myers, Florida to take part in the annual pilgrimage to spring training. Nearly 1,000 miles away from where his story began on Nonnewaug’s campus, Maki understands that his first step in coaching was perhaps the most difficult.

“The arts is a similar field,” Maki noted about his choice in careers. “There are things that people choose to do that virtually guarantee that you aren’t going to make a living, but you know you’ve got to have the nuts to do it.”

After his first full season as the Twins’ pitching coach in 2023, Maki led his staff to the best strikeout-to-walk ratio in MLB. The Twins won the American League Central Division and advanced to the playoffs, where they beat the Toronto Blue Jays in the AL Wild Card Series before falling to the Houston Astros in the AL Division Series.

“It was very exciting,” Maki said of the playoff run. “It was also very fun to watch some very accomplished pitchers and competitors do their thing on a grand stage.”

As Minnesota hopes to return to the postseason this October and make a deeper run, Maki said he’ll seek to see similar success with regard to pitchers’ control.

“I think it’s just a continuation of what we did last year,” Maki said of his goals for 2024. “I was really pleased with our guys. We had the best strikeout-to-walk ratio in the league; that’s important to me, and it has been to me since I was working in college at Columbia or New Haven. It’s going to be tough to repeat [this season]. If I could choose anything from last year to repeat from a statistical standpoint, it would be that.”

“Play Ball,” Not “Work Ball”

While there’s tremendous celebrity that comes with being at the big-league level, the pressure of the job is unrelenting. This pressure has the power to turn a game he loves into a veritable stressor.

“There’s a lot on the line; the stakes are very high in a multi-billion-dollar industry,” said Maki, “and if you let the weight of that get to you, you get too tight.”

The pressure doesn’t just roll off once players and coaches leave the dugout, and Maki doesn’t hesitate to factor this into his coaching.

“It gets pretty noisy literally and figuratively, and by figuratively I mean, now you are doing this to provide for your family,” Maki said. “All these guys have teams of people, they got their agents, they got their representatives for different providers of gear and apparel and media appearances and social following.”

With the pressure of social presence and performing in front of millions of people, all while trying to provide for family, Maki knows the importance of remembering why he and his players love the game in the first place.

“I’m a fan of Major League Baseball. I have been since I was a kid,” Maki said, reflecting on what makes his position in Major League Baseball so surreal. “There are moments that happen quite regularly where I say, ‘I got a great seat for a Major League Baseball game and I didn’t have to pay for it.'”

Maki has always had a deep passion for baseball and has not lost sight of how to still find joy in the game while also being a professional.

“That’s part of our job as coaches to make these guys realize it’s a game, and sometimes you have to return to the root of why anyone does it,” Maki said. “Why do you play? Why did you get into it in the first place? Reconnecting with those roots of why you do it in the first place is very necessary at times for major league players to revisit.”

For Maki, those roots have found their way through a labyrinth of stops, and the roots that allowed big-league dreams to blossom began in Woodbury.

“It’s nice to reconnect with my home base,” Maki said.

And Maki hasn’t forgotten where he came from – before the Nonnewaug baseball team won the 2023 Class M state championship, he sent the team a video of encouragement prior to the opening round.

“The more important the games are, the more loose you’ve gotta be during the game,” Maki told the team. “Prepare and take your work seriously leading up to the game, but once that game starts, man, you should be smiling, laughing, having fun, or else why do we do this in the first place? I’m here up in Minnesota working for the Twins, so I like to have fun at work.”

“They say ‘play ball,’” Maki concluded, “not ‘work ball.’”